Switching Gears: Data Structure Change Behind Stoplight 4.0

Stoplight is a ruby gem that implements the Circuit Breaker pattern. This design pattern enhances system stability and resilience by preventing a service or component from repeatedly attempting a failing operation. The Circuit Breaker monitors interactions and temporarily stops further attempts when a certain threshold of failures is reached. This allows the system to gracefully handle faults, prevent overloading of resources, and provide fallback mechanisms. When conditions improve, the Circuit Breaker resumes normal operation, helping to maintain system availability and prevent cascading failures. These stopping and resuming states are commonly referred to as the “open” (“red”) and “close” (“green”) states, respectively.

Historically, Stoplight gem would count all errors without considering the timing of occurrence. For instance, imagine having an application that occasionally contacts an external payment gateway to process transactions. Due to the infrequent nature of these transactions, the payment gateway may fail in a small number of cases. Suppose the Circuit Breaker does not evaluate the time context of errors. In that case, it may interpret these occasional failures as an indication of a consistently problematic service and open the circuit, preventing further requests to the payment gateway even when it is operational.

The recent Stoplight 4.0 release introduced a new way of counting errors. The sliding time window for error counting helps Stoplight understand whether errors are part of a larger issue or simply sporadic glitches.

This post describes the evolution of Redis data structures that Stoplight uses under the hood. We’ll explore the data structures used before this release and the underlying data structures that allowed us to implement the sliding time window feature.

Redis as a Data Structures Store

Redis is often referred to as a “data structures store.” While it is commonly known as an in-memory key-value store, Redis goes beyond simple key-value pairs and offers a wide range of complex data structures that can be used for various scenarios. This allows developers to choose the most suitable data structure for their specific use case, enabling efficient and flexible data storage, retrieval, and manipulation.

Redis Data Structures in Stoplight Prior Version 4.x

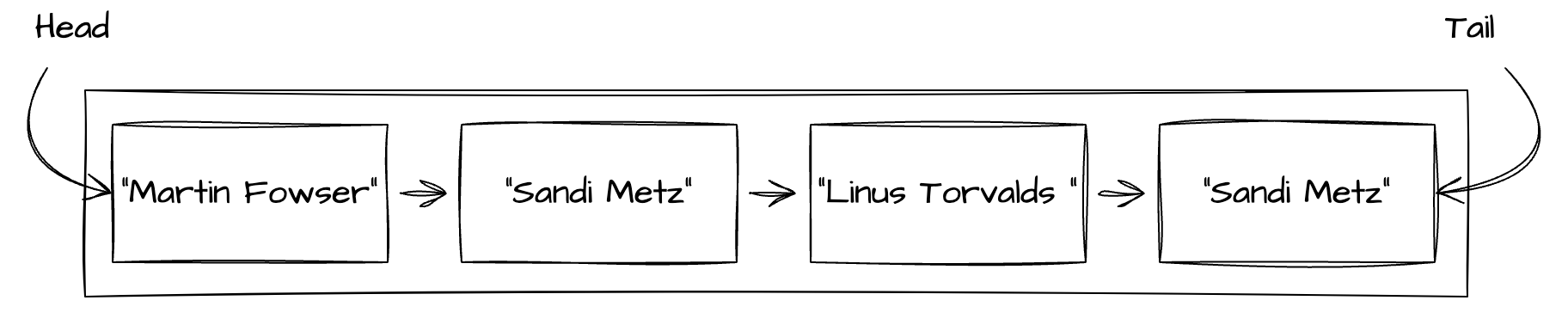

Stoplight 3.x relies on Redis Lists data structure, which essentially is a Linked Lists of string elements that allow for constant time addition of new elements to the head or tail, irrespective of the list size. Let’s explore how Stoplight utilizes this data structure.

light = Stoplight('test-light') { raise "whoops: something went wrong" }

light.with_threshold(2)

We created a Stoplight instance and configured it to open the circuit breaker after encountering two failures. Let’s run it!

light.color #=> 'green'

light.run #=> fails with RuntimeError, "whoops: something went wrong"

We configured our block of code to always fail, and no surprise, the Stoplight failed with an error. Since this is a fresh green instance of Stoplight, it runs the code block immediately. As soon as an error happens, it serializes this error to JSON and performs two Redis commands:

LPUSH stoplight:failures:test-light '{"error_class": "RuntimeError", "error_message": "whoops: something went wrong"}'

LTRIM stoplight:failures:test-light 0 1

The LPUSH command inserts a specified value (a serialized JSON error) at the head of the list stored at stoplight:failures key. If the key does not yet exist, it is created as an empty list before the push operation. The second command (LTRIM) aims to maintain a maximum of threshold errors (elements with indexes from 0 to 1 in this case). This housekeeping operation helps Stoplight retain the necessary number of errors to determine the circuit breaker state. The circuit breaker opens after the second error with the threshold set to two.

light.color #=> 'green'

light.run #=> fails with RuntimeError, "whoops: something went wrong"

light.color #=> "red"

When the block fails twice, Stoplight executes the LPUSH and LTRIM commands again, and the circuit breaker opens, causing the Stoplight to turn red. The light’s color is not stored in Redis, but the state is calculated for every light.color call to ensure synchronization across all application instances of your application. Let’s take a look how the Stoplight’s color is calculated.

LRANGE stoplight:failures:test-light 0 -1

HGET stoplight:states stoplight:failures:test-light

The second HGET returns the value associated with the stoplight:failures:test-light field in the hash stored at the stoplight:states key. Stoplight allows you to lock the circuit breaker (e.g., manually set it to green (closed) or red (open). The lock statuses are stored in this key, and as a first step, we check whether the light is locked to any color. If not, we use the result of the first LRANGE command, which returns all elements of the list (from 0 to -1) stored at the stoplight:failures:test-light key. Then Stoplight compares the number of returned failures with the threshold. If the number of errors exceeds the threshold, the light is red; otherwise, it’s green.

Now, let’s examine what occurs when you invoke the code block while a Stoplight is in the red state.

light.color #=> "red"

light.run #=> fails with Stoplight::Error::RedLight

light.color #=> "red"

It verifies the color by following the procedure described above. As the color is red, it bypasses the execution of the block and immediately raises the Stoplight::Error::RedLight error. What if our block of code executes successfully? In that case, the Stoplight clears all the failures associated with the light:

LRANGE stoplight:failures:test-light 0 1

DEL stoplight:failures:test-light

The first LRANGE command returns the specified elements (from 0 to 1) of the list stored at the stoplight:failures:test-light key. These errors are used only for logging purposes. The second DEL command removes the stoplight:failures:test-light key, clearing all the stored failures in this way.

Congratulations! You now have a solid understanding of how Stoplight version 3.x works. You’ve learned about foundational data structures and their interactions, such as Redis Lists storing error information and commands like LPUSH, LTRIM, LRANGE, and HGET. With this knowledge, we can switch to the latest Stoplight version to view the necessary changes for supporting sliding time window functionality.

Redis Data Structures in Stoplight 4.x

Stoplight 3.x stores failures in Redis List as JSON strings. The List interface allows fast head or tail element retrieval, but for sliding window error counting, it’s not enough to know the element’s index; we also need to know when the error happened. This information could be included in serialized failure, but requesting failures from the past X minutes would require scanning the whole list.

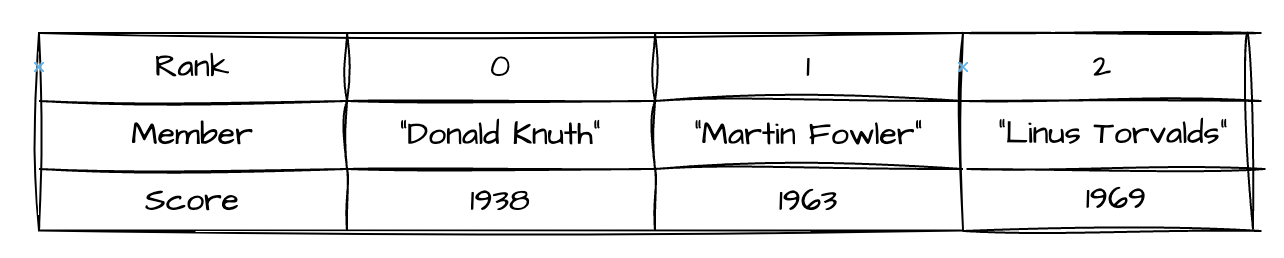

Stoplight 4.0 uses a different data structure under the hood to overcome this limitation. A Redis Sorted Set is a collection of unique strings (members) ordered by an associated score. You can think of sorted sets as a combination of a Set and a Hash. Sorted sets are made up of unique, non-repeating string elements, like sets. However, the difference is that while elements in sets are not ordered, every element in a sorted set is associated with a floating point value called the score, similar to a hash where every element is mapped to a value.

Stoplight 4.x orders errors by timestamp using a sorted set that stores serialized errors with the error time as a score. Let’s follow the same path of the failing code block we examined in the previous section and take a closer look at the underlying usage of the Sorted Set.

These examples will use the new, improved syntax for Lights construction introduced in Stoplight 4.x. Previously, we passed the code block directly into the Stoplight() function, but now we pass it into the run method.

light = Stoplight('test-light')

.with_threshold(2)

.with_window_size(300)

light.color #=> 'green'

light.run { raise "whoops: something went wrong" } #=> fails with RuntimeError, "whoops: something went wrong"

This stoplight will open after two consecutive errors within the last 300 seconds. When an error occurs, it is immediately converted to JSON and four Redis commands are executed.

ZADD stoplight:v4:failures:test-light 1692567961 '{"error_class": "RuntimeError", "error_message": "whoops: something went wrong"}'

In this example, the ZADD command adds a JSON-serialized error to the stoplight:v4:failures:test-light key and associates it with a score represented by a UNIX timestamp for August 20, 2023, at 23:46:01 (1692567961).

ZREMRANGEBYSCORE stoplight:v4:failures:test-light 0 1692567661

ZREMRANGEBYRANK stoplight:v4:failures:test-light 0 -3

The two commands perform housekeeping. The ZREMRANGEBYSCORE command removes all elements of the stoplight:v4:failures:test-light sorted set with a score between 0 and 1692567661, which represents 300 seconds before the error time, thus removing all errors that occurred outside of the 300-second sliding window. The ZREMRANGEBYRANK command removes all elements except the latest two (since we configured the window size to two).

ZCARD stoplight:v4:failures:test-light

Finally, the ZCARD command returns the cardinality (the number of elements) of the sorted set. This number is used for logging and sending notifications.

Let’s take a look at how Stoplight calculates the color of the light when light.color is called. In order to proceed, we need to obtain information on all failures and locked states.

ZRANGE stoplight:v4:failures:test-light inf 1692567661 REV BYSCORE

HGET stoplight:v4:states stoplight:failures:test-light

This is a tricky query for requesting elements of a sorted set. Let’s deconstruct it in reverse order: from the end to the beginning.

- The

BYSCOREoption tells Redis that we are querying elements of the sorted set by score, not by their order. - The

REVoption instructs Redis to perform the search in reverse order. In Stoplight 3.x, we used a List to store failures. The most recent failures were at the head of the list. Now we store errors in a Sorted Set and sort them by time, so the most recent failures are at the end of the set. TheREVoption allows us to maintain the same interface, returning recent errors at the beginning. 1692567661is a timestamp of the beginning of the range (the start of the sliding window)inf(infinity) is the end of the range.

The combination of REV and BYSCORE options perform a reverse search by error time, returning elements at the end of the set first. Stoplight compares the number of errors with the threshold. If the errors meet or exceed the threshold, the light is red; otherwise, it’s green.

In the previous section, I explained how the HGET command works.

Let’s examine what happens when a block of code executes without errors:

light.run { "ok" }

The Stoplight will clear all failures related to the light:

ZRANGE stoplight:v4:failures:test-light inf 1692567661 REV BYSCORE

DEL stoplight:v4:failures:test-light

The familiar ZRANGE query returns all failures within a sliding window. This information is used for logging and notifications. The second DEL command removes the key, clearing all stored errors.

Conclusion

We shed light on the technical reasons for transitioning from Redis Lists to Sorted Sets as an underlying data structure for Stoplight.

Version 3.x of Stoplight used Redis Lists to store error information, which allowed for quick addition and retrieval of elements. However, this approach did not include the time context to implement sliding window error counting.

With the release of Stoplight 4.0, a significant transformation occurred. Redis Sorted Sets were introduced as the underlying data structure to drive the sliding time window error counting feature. This update enables more accurate error time tracking, allowing developers to opt-out.

Redis is a powerful tool for developers, thanks to its wide range of data structures you can utilize in various ways. Whether using Redis’ key-value store, hashes, lists, sets, sorted sets, or even a HyperLogLog data structure, plenty of options are available to suit any project’s specific needs.